CASE STUDY: MEDICSANA – DESIGN + DEVELOPMENT

It was November 13, 2015, and things were not going well…

Our CTO, Jonathan, and I had just gotten off the phone with the general manager of the development shop (I’ll call them “The Studio”) we’d hired to build the MVP of the MedicSana app: they were on their 6th month of a “two month” project. Again, they promised that everything would be wrapped up in another “two weeks,” but we weren’t buying it – even after several scope-reductions so far, they were maybe halfway done with the product, and my latest QA pass through the simple app had yielded more than 120 tickets.

The total project cost was to be dirt cheap, but we were paying for it with missed deadlines that could have cost us the company. The ideal situation would have been to fire them and move on, but it wasn’t that simple: our bank account was starting to run low and the financing agreement with our investors required us to hit a milestone to unlock the next tranche of cash. Progress with our contractors was slow, but, with no front-end developers of our own, firing them would grind progress to a complete halt.

Jonathan and I talked it out for a while: without replacements – which could take weeks – we would have to stick out the engagement. We pulled our code in-house (in case things got ugly) and quietly start looking for our own in-house front-end developer. Now we just needed to find some way to squeeze productivity out of the current agreement with the Studio in the meantime.

It was about predictability, not velocity… predictability is important to the business.

Why was this shift important? It was about predictability, not velocity. While we did see a gradual increase in our velocity over time, predictability is important to the business. Conversations with stakeholders – marketing team, early signed-up customers, investors, and technical partners – is a complex choreography, and it is impossible to manage that choreography with an opaque development process. Yes-Man Syndrome was already creating rifts between the product side of the company and marketing, and causing several “we need another month” conversations with potential partners. In a company so small, the ripple effects were massive.

Our issue did not appear to be a lack of talent, but a communication bottleneck based on their internal hierarchy – it was the workflow that needed to be mended. While I got to work refining and organizing our hiring process, Jonathan took a quick two-day Scrum training course. On the phone a week later, donning new titles – Product Owner and Scrum Master – we informed the Studio that some new processes were going to be put in to place. First and foremost, we would be pulling project management in-house. After shifting the engagement from a “project” deliverable to more of a “staff augmentation” arrangement, we got down to work.

This Post

The rest of this write up goes into the details of how we managed our scrum process with a completely remote team, and, after a few weeks, were able to consistently hit our story-point targets. This is a long and detailed essay intended for readers with a little bit of experience in software development projects (there is some industry jargon, a lot of messy “sausage-making” screen shots).

If that isn’t your thing, no worries, check out some of my writings on the other aspects of the MedicSana Project.

Tools and Team Members

It is easy for us to fall into the trap of valuing tools based on the artifacts that they create. We’ve found, in the project management context for a lean startup (where deliverables are code, not presentations), it is better to think about tools as a way to make communication faster and more natural. Communication is always heavily dependent on context, so it usually takes a close analysis of a team’s workflow to understand what type of tool can improve it.

Our Tools

I’ll be going into more detail about how we used them, but real quick, our main tool box consisted of Hipchat, JIRA, Confluence, Bitbucket, Mural, Hockey-App, and Telecine among others. For a full list, check out my tools list on a separate page.

Our Team

At the time, our team consisted of Jonathan, our CTO who wore many hats, but his main project, with the help of one contracted resource in India, was building out our back-end. I had designed most of the system up to that point, but by then had brought on Luis, a talented designer to take on a good deal of the design documentation. Luis and I also took on QA partially out of necessity (we had a tiny team) and partially because though our research, we were the best versed in the needs of the user. A few months later, we would hire on Christian to work on the front-end and really help us further shift the center of gravity back ‘inside’ the company. The Studio did have a team of talented developers, one in particular that was assigned to our project.

Our Scrum Process

Every team, challenge, and situation is different – there is no universal “right” answer for organizing a workflow, and the best teams evolve over time. I’ve, personally, read many accounts of how teams organize to become successful, and many of them were enormously helpful in iterating through our own process. My hope is that this specific example of this specific team will be useful to others.

Sprint Cycle

We opted for a one-week Sprint Cycle. There are a lot of things to weigh when choosing the length of a sprint, but since we were first starting out, we wanted to get several cycles into a short amount of time for faster process refinement. By holding a retrospective every week, we’d were able to quickly address the problems that we knew would crop up.

In particular, we had already identified communication as a problem for our project – the developers in the Studio were simply reluctant to talk to us. Sprint planning and retrospective activities opened the dialog with the developers directly (allowing us to circumvent the “telephone game” we were previously playing with their project manager) as well as get them to come forth in the beginning if they didn’t understand an aspect of the designs.

Another problem that we faced was Yes-Man Syndrome. The Studio’s culture tended to severely over-promise and under deliver, particularly when it came to time management. Yet, regardless of this consistent pattern of failure, the project management side of their organization continued to over-promise! Without their own culture of self analysis, however, it was asking a lot of the Studio to articulate the specific problems that led to the shortcomings.

Using JIRA with a short sprint cycle, we could quickly demonstrate this tendency in a concrete, visual way, find the problem points, and address them directly. When the team has to talk about under performance at a retrospective, we’re all a little more attentive the next day planning the next sprint.

Sprint Planning Meetings and Prioritization

We held our sprint planning meetings every Wednesday and they tended to last about 2 hours. Being remote, we alternated between Skype, Google Hangouts, and a partner’s product, VSee (depending on which was working better that day) and used Mural as a visual aid.

Preparation

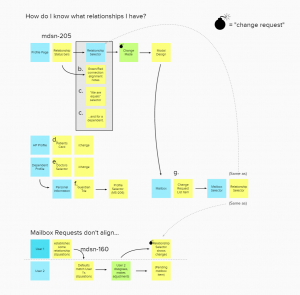

As the “Product Owner,” I prioritized user stories on the Mural board before each meeting. JIRA is great for somethings, but it is a terrible interface for organizing a backlog, so I would use the Mural board to organize tickets that were not part of a sprint process yet. I never got to a completely linearly-stacked tickets, and that was quite alright. Choosing tickets for a sprint should first be thought about in terms of business prioritization, but the final decisions need to be made by the team. My initial prioritization – and generally a broadly stated goal – would be enough to get started.

As the “Product Owner,” I prioritized user stories on the Mural board before each meeting. JIRA is great for somethings, but it is a terrible interface for organizing a backlog, so I would use the Mural board to organize tickets that were not part of a sprint process yet. I never got to a completely linearly-stacked tickets, and that was quite alright. Choosing tickets for a sprint should first be thought about in terms of business prioritization, but the final decisions need to be made by the team. My initial prioritization – and generally a broadly stated goal – would be enough to get started.

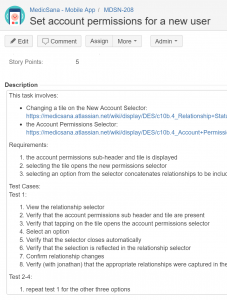

It is good to have the “Requirements,” “Test Cases,” and a good 80-90% of the design work done for high-priority tickets before the scrum meeting starts. Things will change in the meeting (if it is a good dialog) but it is always easier for the team to respond to something concrete rather than have a group discussion about an abstract intent.

Getting the Meeting Started

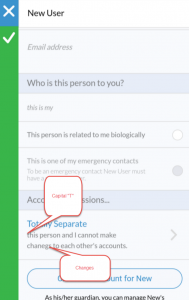

When everyone was on the call, I would express a goal for the sprint. Generally this would be a tactical goal, “We want to test the “create user” functionality with our test group next week, so I have prioritized these 5 tickets that all have to do with that process.” It is up to the team to decide whether this will be possible, but a team that understands your intent is more likely to creatively design a plan to accomplish it and point out ways to do things more effectively.

Story Point Allocation

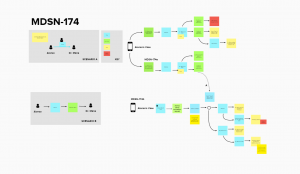

Before assessing effort, it is necessary for the team to understand the story fully. Using Mural board for this conversation was useful because explanations could quickly become visual. Often, these involved quick hack-jobs of previously made wireframes as conversations evolved.

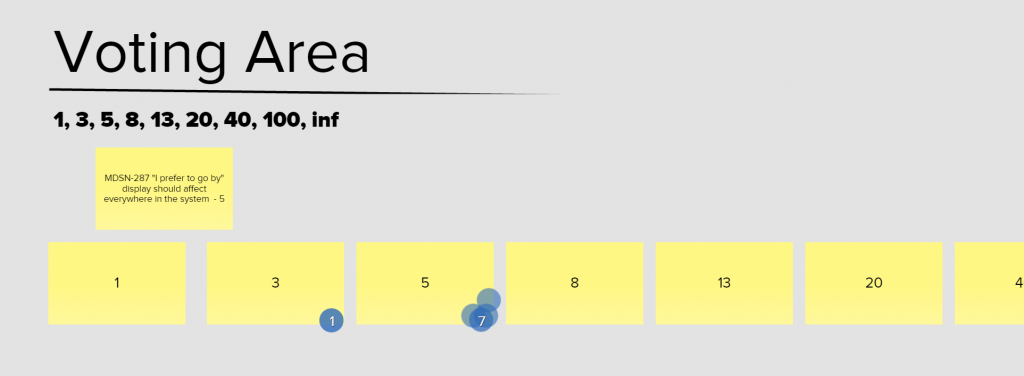

Story points are the relative amount of “effort” that the team believes a user story will take. The team votes on the number for the effort of a story (so an easy task may be one story point, while something that includes a lot of technical challenges, ambiguity, or team choreography may be an 8), then decides on how many user stories can be pulled into this sprint.

To vote, the team would use Mural’s “Vote” function to vote on the number of story points. The system allows anonymous voting, so we would lay out the numbers (see above) and everyone would vote on the effort.

Adding to the Sprint

Next, as a team we would discuss the stories to add to the sprint. Our team generally averaged 26 storypoints per week, but adding up the storypoints was only the first factor. It is also important to make sure that too many stories aren’t relying on one person as a bottleneck – for instance, if all of the sprint’s stories require Jonathan to make back-end changes before beginning, the whole team will be blocked. Another thing to keep in mind is the skill level of the team. The Studio had a very junior level developer pitching in, and while he may be able to knock out 5 one-point stories in a week, he generally didn’t have the skills to coordinate a 5-point task.

Next, as a team we would discuss the stories to add to the sprint. Our team generally averaged 26 storypoints per week, but adding up the storypoints was only the first factor. It is also important to make sure that too many stories aren’t relying on one person as a bottleneck – for instance, if all of the sprint’s stories require Jonathan to make back-end changes before beginning, the whole team will be blocked. Another thing to keep in mind is the skill level of the team. The Studio had a very junior level developer pitching in, and while he may be able to knock out 5 one-point stories in a week, he generally didn’t have the skills to coordinate a 5-point task.

Requirements and Test Cases

The last part of the meeting was spent reviewing (or, in many cases, writing) the Requirements and Test Cases for each task. In my personal opinion, this is an art rather than a science, and can walk the line between formality and informality. There is a natural tendency for developers to want requirements to be as detailed as possible, but specifying every detail in written form is a tedious process and – to a designer – feels redundant if you’ve already annotated wireframes. It is also generally impossible to anticipate every detail of a system before you can feel it in the code.

Generally speaking, we went with a minimum-viable documentation philosophy and concentrated on improving 1-on-1 communication channels between team members. When things were simple, we wrote out more documentation so that team members could work more independently on them. For more complex ideas, we would just make a note to have a skype conversation with the designer when a dev picked up the ticket.

This method was awkward at first, but after a few sprint cycles greatly improved the accuracy of the first iteration of a build. At the end of the day, we’re all human, and humans evolved dialectic long before written communication.

In the Sprint

With the planning done and the Sprint Backlog stocked, it was time for the push and pull of getting work done. The day to day of the project focused primarily on communication, but there were a few specific things that we found to be useful to think about in more depth.

Documentation

The first task in the sprint was to identify design holes that needed to be filled. Often we would design most of the details of the system ever cognizant that things would change as soon as we started talking to the developers in more detail. I have a more detailed overview of our design language and documentation philosophy in this post which may be of more interest to designers. The important thing to remember about documentation is it’s purpose: it is a communication tool, not a beautiful artifact. With few exceptions, once the first iteration of a design is in code, the original documentation is out of date and can be discarded.

At MedicSana, we initially used Adobe Illustrator for site maps and flow diagrams, but as we switched to agile realized that the collaborative capabilities of Mural made it a more effective tool (Mural certainly isn’t as pretty and clean as a well laid-out illustrator diagram, but communication, not beauty!).

]We continued to design screens in Illustrator as it was the fastest program for Luis and I (I have a Windows machine, so I can’t use Sketch… I hear it is great). Generally speaking, I’m a fan of the differentiation between a “Visual Designer” and an “Interaction Designer,” but in a start-up, a designer generally needs to wear more hats! We kept an up-to-date “Visual Design” illustrator document that had each page style, icon, and common elements (such as generic buttons or toasts). This is a handy document to keep open in a separate tab to make designing new user stories faster while staying in the design language.

For more confusing interactions, or things that we wanted to talk with users about before jumping into code, we used Invision Prototyper. Interestingly, we had also invested in a license for JustinMind Prototyper, which has a lot more functionality and would have enabled us to build more high-resolution prototypes, but the program was too cumbersome for our process. Again, the goal was a quick communication tool, and sometimes a quicker, lower-resolution prototype is all you need to get the point across in less time.

Feedback

Once the first iteration of a story was done, the devs pushed it to a new version of the app through Hockey App. Since everyone on the team had an instance of Hockey App installed (some of us on both an iPhone and Android) we could all easily QA test issues.

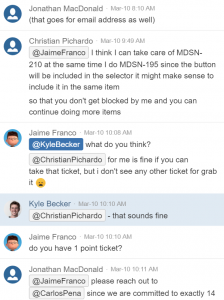

By the time a story was in code, there really isn’t much sense using Confluence as a communication mechanism (unless a problem needs to be completely rethought). At this point, the JIRA ticket was the primary source of record. For simple problems, I’d take a screenshot of the issue on my phone, send it to myself through Hipchat, and then use Snag-It to comment on the problems. For more complex issues, we’d use the Telecine App to record a video the problem, then note the time in the video of corresponding comments.

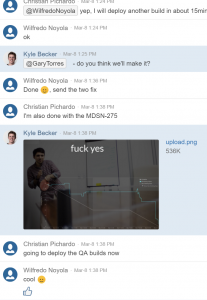

We soon learned that it is fastest to actually communicate in two ways. If a problem is small, talking to a dev on Hipchat about it is the best place to start – that way, they can get started working on a fix right away to get it into the next build. It is still important, though, to get the details into a ticket so that the issue doesn’t get lost in the chaos of day-to-day activity. It is important to know when a ticket failed, why it failed, how quickly it was resolved, and when it was re-submitted to QA. These details may feel gratuitous, but because JIRA tracks the timing of these events, it makes problems easier to identify and discuss in retrospectives.

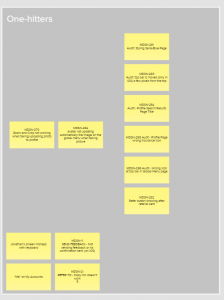

“One-Hitters”

Though we constantly work to reduce them, there are inevitably times when internal dependencies “blockers” developers. One way that we found to keep forward momentum was with our “One-Hitter Bucket.” When we brought the code in-house from our contractors, it was absolutely riddled with small errors. By keeping a stack of these little, 1-story point bugs handy, we were able to keep people busy during their blocked time. Because the Studio had an intern on the project, these simple tasks could also keep him busy with tasks that improved the project but didn’t block everyone else.

Though we constantly work to reduce them, there are inevitably times when internal dependencies “blockers” developers. One way that we found to keep forward momentum was with our “One-Hitter Bucket.” When we brought the code in-house from our contractors, it was absolutely riddled with small errors. By keeping a stack of these little, 1-story point bugs handy, we were able to keep people busy during their blocked time. Because the Studio had an intern on the project, these simple tasks could also keep him busy with tasks that improved the project but didn’t block everyone else.

One-Hitters had another advantage: they were great for morale. As we pulled them in during the sprint, the team could pick up a few extra points that added to the total output of the sprint.

One-hitters need to be balanced, though – people love one-hitters because they’re easy wins, but they weren’t prioritized in the initial sprint for a reason: by definition they aren’t that important. As the product owner, I made it my task to dole out the One Hitters, and ONLY when it was clear that someone was legitimately blocked from working on something more important.

Review + Retrospective

We held retrospectives every Tuesday at the end of our sprint. Our retrospectives generally consisted of the standard activities: Demos, review of the burn chart, and a retrospective activity and discussion about how to improve our process.

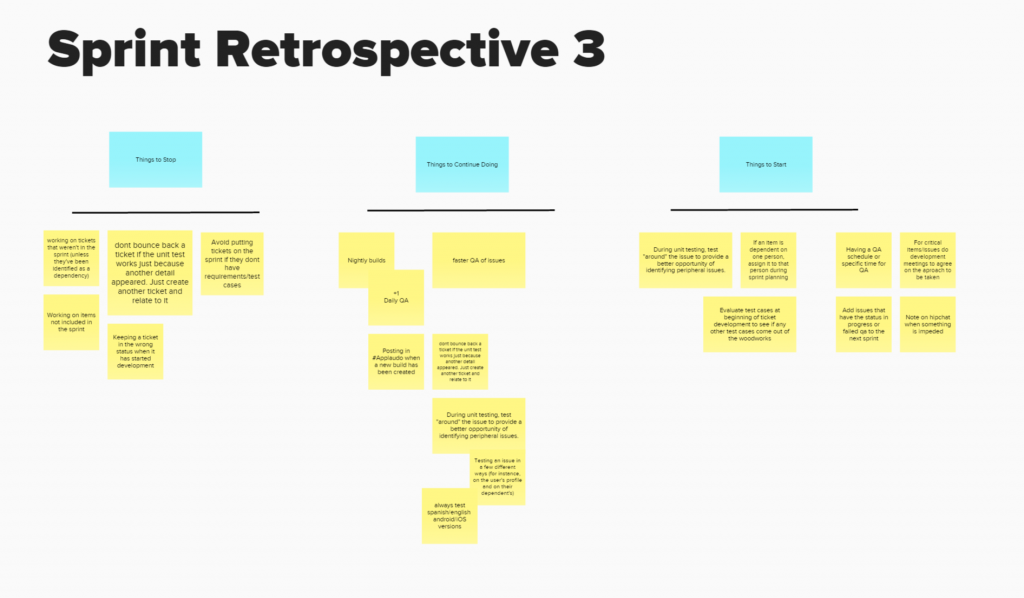

We generally stuck to an activity that we conducted in Mural where we would talk about things to “Stop Doing, Start Doing, and Continue Doing.” Most of the time, the discussion focused around the subtle balance between asynchronous communication (in the JIRA ticket? On confluence?) and synchronous communication (skype, Hipchat, etc…).

Opening up the dialog allowed us to experiment with different solutions. For example, because our sprints were so fast, we had problems early on keeping tickets moving through QA (a bunch of tickets would fail the day before the sprint end leading to frantic last-minute fixes. There were also miscommunication quirks as a dev would finish a ticked and move it to “Ready for QA” in JIRA, but because it was not merged into the latest build, the ticket would fail.

Open retrospectives allowed the team to attack each problem on multiple levels, these specific problems were resolved when we made several changes:

- Process: We added a “Ready for Staging” column in JIRA to give devs the ability to communicate their completion without confusing the QA process.

- Rhythm: We started pushing daily builds through Hockey App every afternoon so that QA could test every morning and fail tickets faster if changes needed to be made.

- Communication: Devs and designers (who were also QA at MedicSana) would screen share more before marking a ticket ‘complete’ – this way we wouldn’t lose 24 hours pushing a ticket to QA and failing it over small discrepancies.

Conclusion

Getting a scrum team up and running is a challenge. Though there are no shortage of resources offering frameworks and advice for the process, but every team faces different challenges and and reaches a state of “flow” with a different set of tools, tactics, and communication paradigms. I do believe that there are a few themes that are universally helpful:

- Be purposeful:

- It seems to be a common belief that because you can’t force a culture that you can’t cultivate it. There are a lot of proactive things that can be done to improve a company culture when you know what to look for. We did a ton of research on building teams and streamlining processes that were a huge help. I wrote a little bit more about my personal philosophy of teams in this article, and have included a list of resources below that I found immensely helpful.

- Focus on Communication:

- From equipment and furniture to organizational structures and simple prejudices there are an infinite number of factors that can contribute to an ineffective workplace. None of these issues can be identified, however, without a healthy flow of communication. When we concentrated exclusively on getting the tools and frameworks into place to enable fast feedback, we were amazed at how much easier the other problems were to solve.

Check below for a list of my favorite readings on the topic and a list of tools, Or head back to the project homepage to view all of my posts about MedicSana, Inc.

Resources

Tools

We’ve played with a lot of tools over the course of this process. Check out my tools list to learn more.

Read More

Read more about the MedicSana project, other design case studies, or more about me on my homepage.