CASE STUDY: MEDICSANA – RESEARCH

After several conversations with my co-founder, it was time to design a healthcare solution for Latino immigrants to interact with and send money to their parents and doctors in their home countries. The only problem? I’m not latino, I’ve never sent money anywhere, and I’d visited a doctor in anywhere but my own home land. I didn’t even speak Spanish!

Our first interview took us down a long, dusty, gravel road in the outskirts of Austin. I’d recruited Jona Barceló, a close long-time friend who was, himself, starting to get into design research and we hit the road as soon as we could get away from our day jobs. After getting lost a handful of times some neighbors pointed us in the direction of the address-less trailer where we met our first participant and his family.

This interview would be a little different than the interviews I’d done with user groups at frog. We’d scheduled the interview with one, male participant, but as would become a theme with most of our interviews, it would be his wife who did most of the talking. Their two kids also gathered around the table to drink coke and watch their parents do card sorts and talk to these two strange guys, one who only spoke English.

As we settled into the conversation, Jona and I were introduced to the familial intricacies that would be the foundation for a unique business proposition.

Why Design Research?

These interviews were conducted at the very beginning of the MedicSana project. While our co-founder had a background similar in many ways to our target market, there were some key differences (such as language proficiency, income level, and technical savviness) that would have a significant effect on our understanding of how to bring a successful product to market. We’d also, by this point, come up with a variety of broad, abstract ideas with potential for this market, but had no way to understand whether our perception of their painpoints would be accurate (and what we may have missed).

Design research can broadly be broken into three categories: Foundational Research (to understand mental models), Generative Research (to co-create solutions), and Evaluative Research (to refine new concepts you want to introduce). At this point in the project, we were just beginning to understand the context and opportunities (…and we had nothing to evaluate), so we structured the interview to focus on foundational and generative activities.

A mental model is an explanation of someone’s thought process about how something works in the real world. It is a representation of the surrounding world, the relationships between its various parts and a person’s intuitive perception about his or her own acts and their consequences. Mental models can help shape behavior and set an approach to solving problems and doing tasks.

Our Interview Structure

Our interviews lasted about 2 hours each (though with some good participants we were able to stretch them further, never underestimate how much people love to talk about themselves to an interested audience). We focused the first 2/3rd of each interview on foundational methods that helped us gain more contextual understanding of our participants’ lives, and the last third discussing possible value propositions with a participatory design activity.

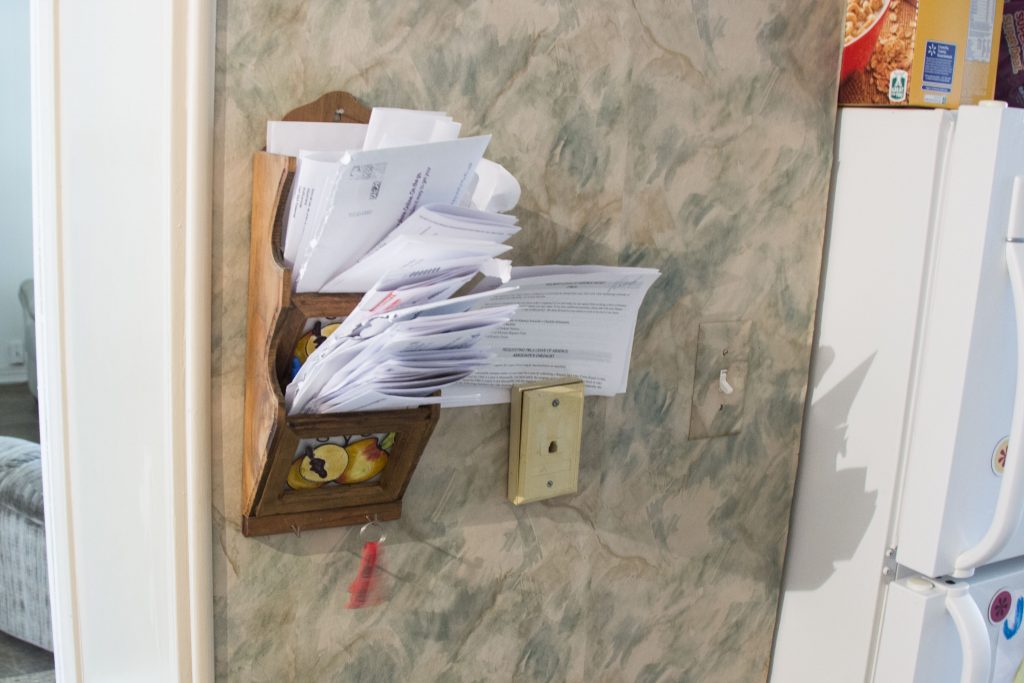

We always did interviews in context which, for us, meant in people’s homes. Not only does this make things more comfortable for the participant (so it is easy for them to open up) but it also gives us the ability to understand the context and constraints of their actions. We were constantly on the look-out for small details that we could ask about that would help us understand a participant’s aspirations, tastes, and mental models.

Open-Ended Discussion Questions

We started with about about a half-hour minutes of guided open-ended discussion questions where we got to know our participants and their families. We structured questions that would allow us to understand the distribution of people’s families across their home countries (our participants were all either Mexican or Salvadoran) and the US, and to understand the cadence and amount of money sent home for both regular and event-specific remittances. We would then talk about medical events and the way the family understands and manages healthcare at home and with extended relatives.

Opening interviews with these general questions had three major advantages for us:

- It builds rapport

- People LOVE talking about their families (whether it is bragging about their children or complaining about their good-for-nothing uncles). Opening the conversation helped our participants warm up to us, building the rapport that we would need later in the interview when we would be asking more personal questions.

- It helps us gain context

- It helped us begin to understand the mental models that people were working with, and get familiar with themes that would be important later. For our group, the layers of responsibility to community, religion, and family are tightly intertwined.

- It introduced us to the players

- Because we were studying the coordination between family members, it became important to us to know the names of parents, siblings, and other family members that we could ask about in our later activities.

Situation Mapping

We then went on to a system-mapping exercise. In our first interview, for instance, our participant’s father had a heart attack (he survived) that landed him in the hospital with his distributed family footing the bill. We had our participants sort through cards representing hospitals, clinics, payment transfer services, and people and arrange them on an abstract US/Mexico (or El Salvador) map. As they constructed their maps, they told us the story in more detail about the flow of money and information (and gossip) in their families.

As with all design research activities, the maps at the end of the exercise made for nice artifacts, but the real value to this activity is the conversation. It is often a little strange for people to talk in detail about such procedural activities, but building a map allows us to see all of the intermingled relationships in this complex choreography and ask specific questions about each interaction.

For instance, in the map on the right, we saw that Mari, our participant’s sister, played a major role in coordinating the family’s action plan in an emergency. Other siblings (“Otros Hermanos” on the “my family” card) played more of a passive role. We found these central figures, such as Mari, to be a common theme across many of our participants once we started building maps and listening to stories.

Design a Service

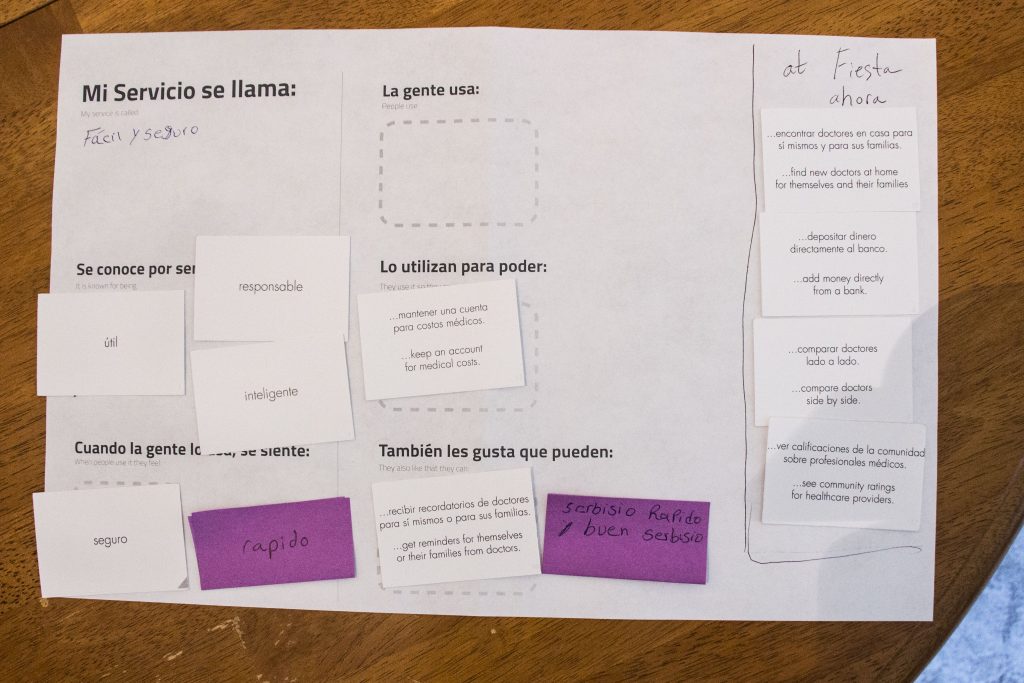

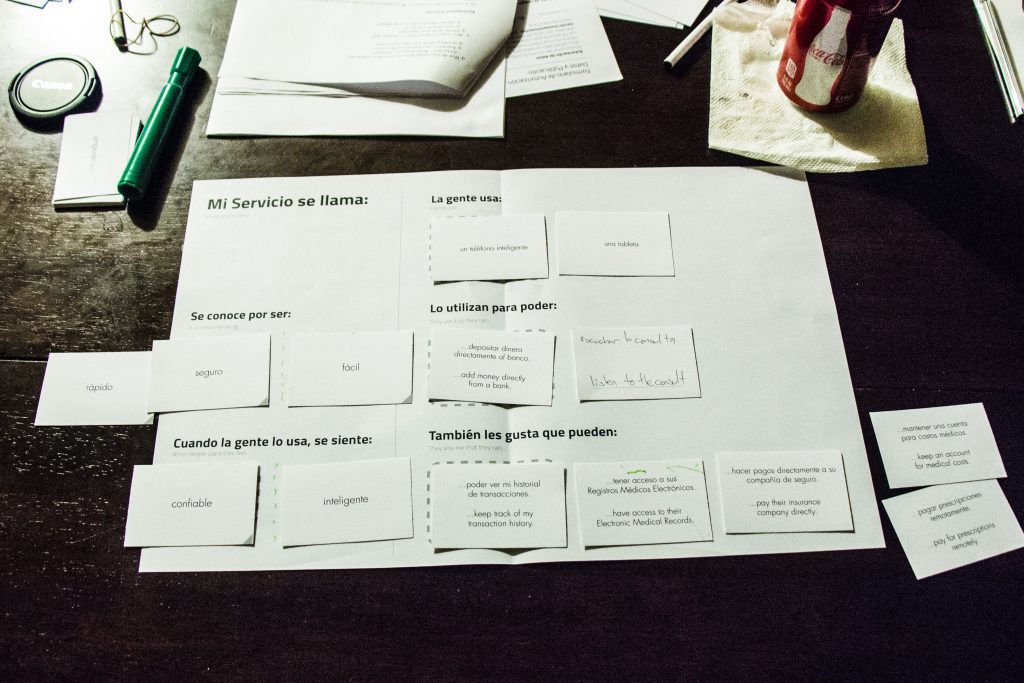

We would conclude our interviews with a generative exercise wherein our participants could build a service. We gave new decks of cards to participants where they could pull out cards (or write their own) to describe what someone would use the service for, what type of device they would use for it, and the qualities of the service that they felt would resonate most with it’s users (did people use the service because it was easy, or because it was secure?) and how people would feel when they used the service (did people use it to feel responsible, or intelligent?).

As our participants sorted the cards, we would have them “think out loud” so that we could understand their thought process. With these activities, one of the most important things is the prioritization, so when a participant chose several cards for a category, we would always force her to choose the most important, second most, etc… and explain her choices.

Since we interviewed couples, there would often be minor disagreements about privatizations which gave us further opportunity for discussion (looking at the pictures, you’ll see there are often multiple cards scattered about so that the husband and wife could have their own prioritizations).

Another important dynamic of prioritization exercises at the end of the interview is that they can uncover important issues that may have been missed in the beginning of the interview. The conversational nature of design research can lead to participants focusing their attention on aspects that they may have an emotional attachment to, forgetting others. Even at the end of an interview, participants can surprise you with some of the things they’ll choose – asking them to explain their logic is generally quite revealing!

Wrapping Up

After each interview, Jona and I discussed the themes we heard, how they related to previous interviews, and sketched possible business model ideas. The value in qualitative research is its ability to unpack the sociological structure of a user group to the extent that personas can be built. Projects, such as MedicSana, that require a critical mass of social involvement benefit from understanding the interactions between different roles in a community. With the stories we heard, we build an entire family of personas that we would use throughout the project to discuss different levels of engagement and important factors for each.

This write-up focuses on the structure of our interviews with this specific group. Be sure to check out our structure for our doctor interviews for the MedicSana project and my more general writings on design research starting with DR 101: What is Design Research?

Read More

Read more about the MedicSana project, other design case studies, or more about me on my homepage.