CASE STUDY: MEDICSANA – DESIGN + DEVELOPMENT

We used to write bibles. Design bibles. After spending months researching a certain user group, a group of designers would gather around, offsite and safely away from our users, clients, and anyone else who may disturb us for several months to design an entire software system. When we emerged, we would have a beautiful 200 page (or more) design spec PDF with every possible screen annotated.

What ever happened to these documents? Did anyone read them? Our designs looked beautiful, but was the software functional? Did it change when the developers got a hold of things? Did it even get built at all? I have no idea.

When we formed MedicSana design bibles weren’t going to work. We had a small team with a tight schedule; we needed to get software built – and quickly! A huge part of switching to scrum was an iterative approach to how we documented UX design elements in a more agile way.

In this series, I started by writing about how we managed our scrum process, a quick article about our (I) philosophy of documentation and the way we documented the guidelines for our (II) design language system. In this article, I’ll write about what the documentation for our User Stories looked like in our scrum process. I’ll use some Scrum jargon in this article, if you’re unfamiliar with the system, here is scrum.org’s official glossary.

The official scrum guide on scrum.org’s website is purposely vague when it talks about “product backlog items,” and while there are countless articles and guide books (some of them immensely useful), there is a general consensus in the agile community that the best type of documentation style for a single task is the the style that your team finds the most useful.

“Agile” is a philosophy of software development that, among other things, espouses the wisdom of “Individuals and Interactions over processes and tools,” and “Responding to Change rather over Following a Plan.”

User Stories

At MedicSana, we used “User Stories” as a model for our for our backlog items. A User Story is a style documentation for product backlog items that represents a feature that a customer might use in a software product.

Ron Jeffries says that a user story consists of three elements: a Card, a Conversation, and a Confirmation with Confirmation being the most important. With this in mind, we began every sprint by writing test cases for a user story, then planning how we would accomplish it. Our Product Owner (me) doubled as a designer and QA tester and our Scrum Master (Jonathan) doubled as a back-end developer, so the whole team was involved in our day to day discussions.

Card

We choose which stories we would accomplish at the beginning of each Sprint. Each story was kept on a “card” in Mural. Mural is an online tool that enables teams to keep an online post-it board. Since the board is always accessible to whoever has a link and enables simultaneous editing, it was perfect for our meetings.

We choose which stories we would accomplish at the beginning of each Sprint. Each story was kept on a “card” in Mural. Mural is an online tool that enables teams to keep an online post-it board. Since the board is always accessible to whoever has a link and enables simultaneous editing, it was perfect for our meetings.

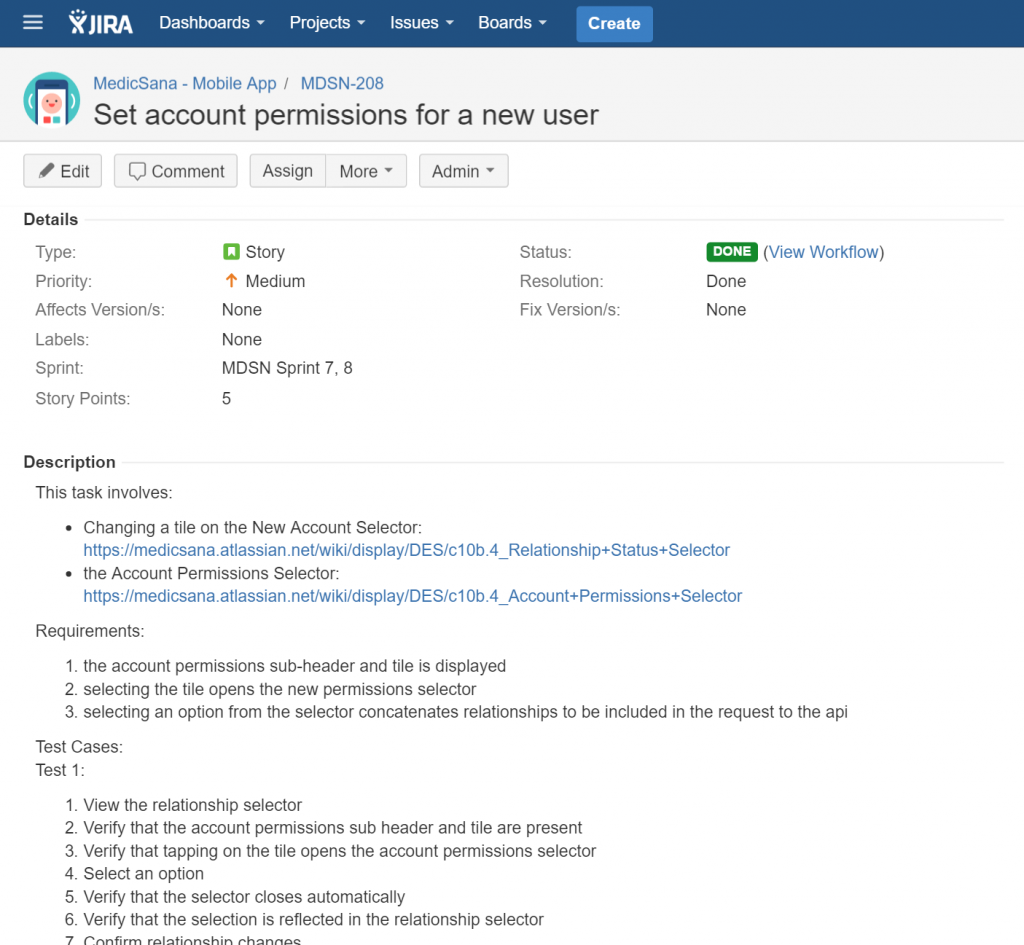

In the first half of our sprint meetings, we would select which product backlog items would be brought into the sprint. As items were selected, a member of the team would create (if needed) the backlog item in JIRA and we would update the test cases and requirements if needed through our discussion.

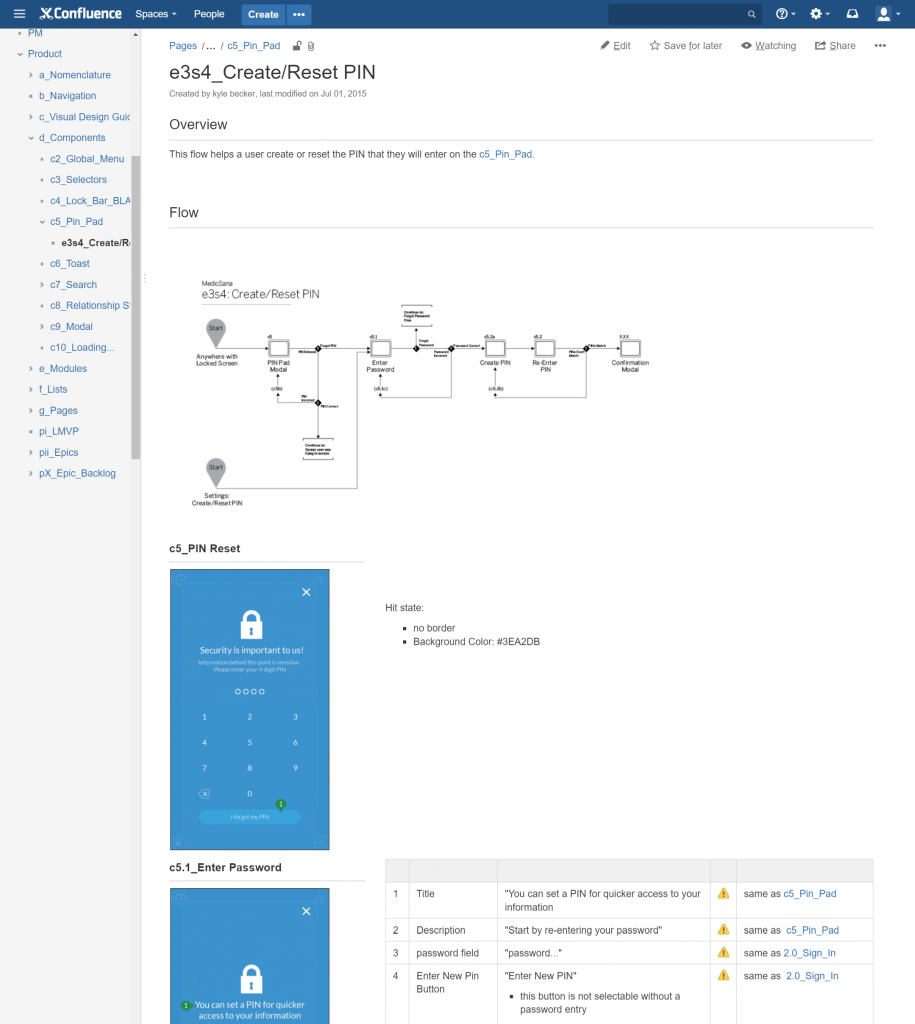

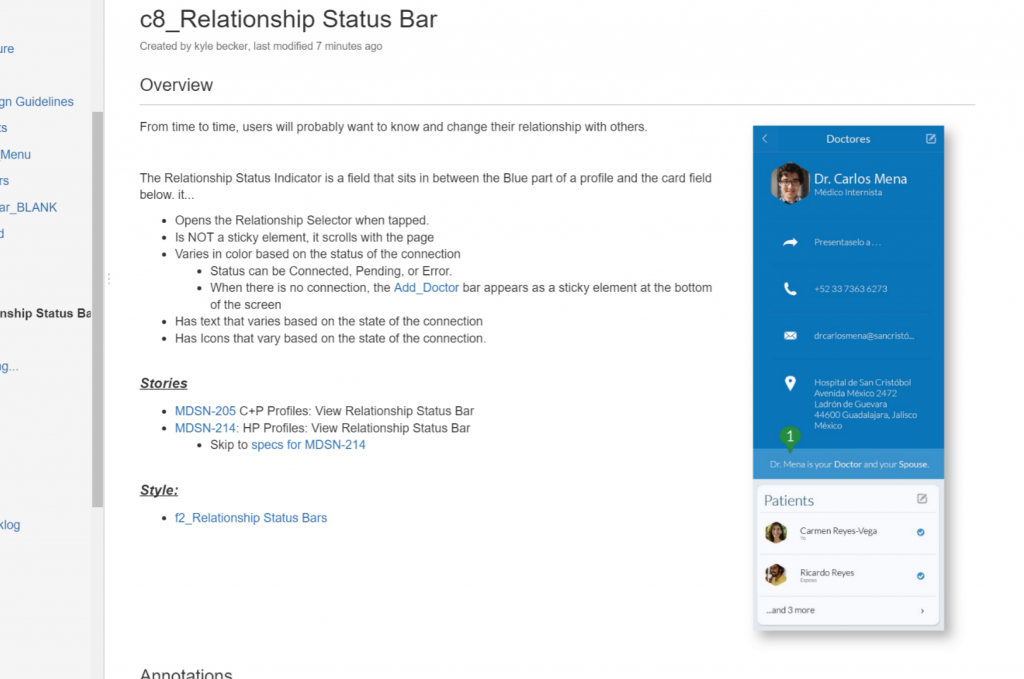

Our design team operated partially outside of the Sprint, so the design specs for user stories were generally about 50-80% ready at the beginning of the Sprint. This both improved the quality of our Sprint Planning conversations and enabled to the dev team to start working on the first iteration in code immediately at the beginning of the Sprint. We captured these designs in Confluence wiki.

During Sprint Planning, we would simply drop a link to the Confluence page into our JIRA ticket and write up the requirements. We would also go back onto the confluence page and update the name of the the designs with the Story. Our JIRA ticket may also contain links to our Design Language System which contains standard visual and interaction patterns that we use throughout the system. This way, our User Story documentation can concentrate on what is different in each flow while maintaining consistency with the rest of the system.

It may seem a little confusing that we use two different systems for our tickets, but this actually worked quite well for the simple reason that the development of the the code and the designs could be worked independently and linked together “just in time” for the sprint to start.

Conversation

Confluence always included the first version of the designs. These generally became out of date a couple of days into the sprint. Why? Because our second iterations were generally in code – it made no sense to look at the old designs any more (and updating them would just be a waste of time).

The question of “when design happens” is one of the aspects of our industry that is currently seeing a lot of friction. I write a little bit more about how “vertical” product development practices, such as Scrum or other Agile methods, can interact with design, a “horizontal” development processes in another article.

So while the Confluence documentation got the Story started, the wiki pages themselves were rarely updated as the “Conversation” emerged through a variety of different channels – Hipchat for the simple stuff, and quick one-on-one calls for more complicated things. These spontaneous meetings generally started with the front-end developer and the designer, but we’d pull others on an as-needed basis.

Our JIRA tickets enabled us to have threaded conversations about specific user stories for times when it didn’t make sense to interrupt someone with a question. JIRA was a much better place for these conversations than Confluence because of the format. We organized Confluence in relation to the system map of the user experience which, helped us understand how the system functioned as a whole, but was more difficult to find specific things quickly (and was also, as mentioned, rendered obsolete near the beginning of a sprint). JIRA was organized to reflect our development process, so to find information about something currently relevant was much easier.

Confirmation

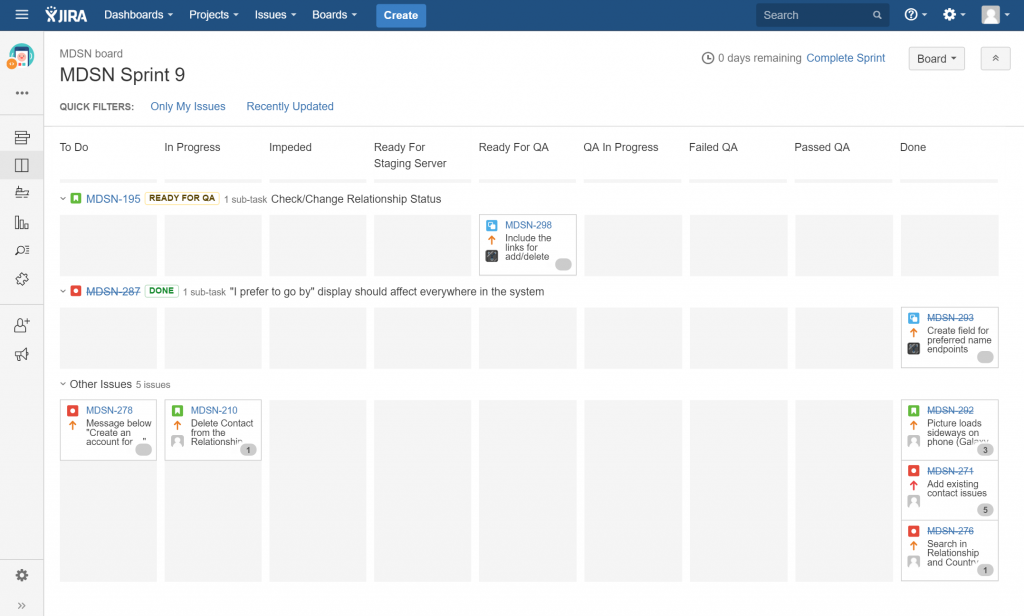

Our stories moved through JIRA in a pretty standard fashion. Over time, we added a few columns for “Ready for Staging,” “Ready for QA,” and “Passed,” and “Failed” to help us track the current status in the moment, and analyze in our retrospectives what parts of the process were creating bottlenecks. I write a little bit more about that in my article on our scrum process.

Since I was the one with the final QA sign off on the functional side (remember, small team, so I was the CEO, Product Owner, designer, and QA tester) “Ready for QA” was often an internal signal that something was ready for me or Luis (our other designer) to look at. QA bugs generally took the form of screen shots of the actual interface with notes added with SnagIt, illustrator, or whatever else was the fastest for the individual tester. We would then drop these tickets back into the “ready” column. JIRA tracks who writes a comment, so the developer would always know who to have a follow-up conversation with when one was needed.

Visual design bugs were another place where our design language system documentation came in handy – we could always just link to the appropriate page when we saw one to help the developer quickly rectify these issues to be consistent with the over all system.

Wrapping up

As with any team, we went through many iterations of team process to get to this point, and there are still countless things we could have done to continue improving. In my opinion, effective communication is the most important thing to optimize on a remote team. Almost all of the workflow changes that we made over time were the result of our team identifying communication breakdowns and brainstorming ways to address them.

When it comes to structuring user stories, the most important aspect has nothing to do with the documentation itself, but the sprint process. The best way to improve user stories is to have regular (and useful) team retrospectives. No documentation system is universally perfect, but a team that has a tight feedback loop will be able to quickly find the system that works best for them.

We noticed in our retrospectives that having JIRA close was a huge benefit. It is easy to say things like “design should document better,” but this type of feedback in the abstract tends to be quite worthless. When the team is able to pull open a past ticket and discuss which parts of the documentation were useful and which were found lacking, team members can make more concrete resolutions for future changes.

I’ve written several articles about different aspects of the MedicSana project, head back to the homepage to see more articles about other topics.

Read More

Read more about the MedicSana project, other design case studies, or more about me on my homepage.