CASE STUDY: MEDICSANA – BRAND

In this write up, I describe the underlying tenets that build our brand strategy. Everything that we’ve created used industry best-practices, such as personas and brand archetypes, as frameworks for synthesizing the insights from our research interviews. In this write up, I’ll describe the family of personas we developed in greater detail. These personas helped us understand and craft MedicSana’s artifacts including:

Getting the Lay of the Land

We knew from our early research and from the insights of our co-founder that there were several remittance channels that were driven – among other things – by a need for families in the US to take care of the healthcare and medical expenses of their parents, nieces and nephews, and other family members.

Our secondary research on El Salvador through Pew and other sources showed that the 16% of our intended launch market’s GDP was remittances from friends and family members in the US. We also found in a study on worldwide remittances that as much as half of remittances send around the world were “intended” for healthcare and medical services.

That “intended” piece was key. What did that mean?

As we got into our own design research interviews with remittance senders in the US we found that it meant a lot.

Many of the people we talked to in the United States sent back money regularly with the hope that their family members would use it for responsible purchases – food, shelter, and, of course, healthcare. Unfortunately, with little transparency into the lives of their family members and the actual expenditures being made, remittance senders often felt that their family members may under-appreciate – or at time out-right take advantage of – the money they were sending home.

Remittance

n. The sending of money to someone at a distance.

n. The sum of money sent.

In fact, most of our core findings on the remittance sending side of things had to just as much with the flow of gossip, peer pressure, reputation, and responsibility within a family as it did the flow of money.

For a more in-depth look at our Brand Tenets, check out our internal Post-Research Brand Tenet Write-Up.

A Family of Personas

While we started working on a traditional “persona” model that classified different “user types” in their own bubbles, we found that in the context of a family – particularly large families like our target market tended to have – this model wasn’t useful off the shelf.

Because our project involved the coordination of groups of people, it wasn’t the tendencies of individuals themselves that we needed to focus on, but the interactions that happened between them.

In a single research conversation, we would see the same persona types appear over and over again; even if our interview participant didn’t play the “organizer” role, for instance, the stories she told would be heavily centered around her aunt, sister, or someone else that acted played the role.

It would be much more useful to think in terms of the network rather than the nodes. Instead of building individual personas, we created a persona family that would house many of the individual persona types as well as the relationships that we found to be themes in our research.

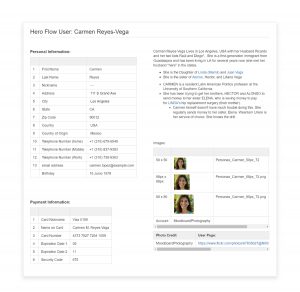

We build our personas around the family of Carmen Reyes Vega. Carmen lives in Los Angeles, California, and has family – her parents, sister, and nephew – in San Salvador.* She also has two brothers that live in the US – Hector who doesn’t make a whole lot and doesn’t really have a bank account, and Alonso, who has done quite well for himself in his career.

Our persona family was also included the family’s doctors, both in their home country and in the US.

*Sometime her family was from Guadalajara, Mexico. We were a little inconsistent.

Our Target Customer

With a family of personas, we could focus on the characters that would have the most influence on the system. By aligning our brand tenets with the values that would resonate most with them, we would have the most leverage on the system as a whole.

We envisioned Carmen’s personality to be very similar to the “organizer” character that we heard in so many research stories. She, in particular, would be our target for the release: if we were able to make Carmen our customer, her sense of responsibility and “Organizer” role in the family would get everyone else in. If we were a success in her eyes, she would also be the most likely person to gossip to her friends in the community about the service (who would also, likely, be Organizers for their own families).

The important thing to remember is that Carmen isn’t necessarily the most wealthy person in her family. If we were targeting wealth, we would have tried to target her brother, the Alonso character. Alonso may use our service if we marketed to him, but he would be less likely to influence the rest of the group. Based on our research, Alonso’s (sometimes reluctant) duty to his family is expressed and enforced through Carmen – she has the power here – and the natural tendency to keep the family in line.

Personas in Practice

Our personas came to life in any instance where we needed to make a decision about either value or constraints. Our persona family, therefore, was a constantly evolving artifact as we did more research and uncovered more questions to answer.

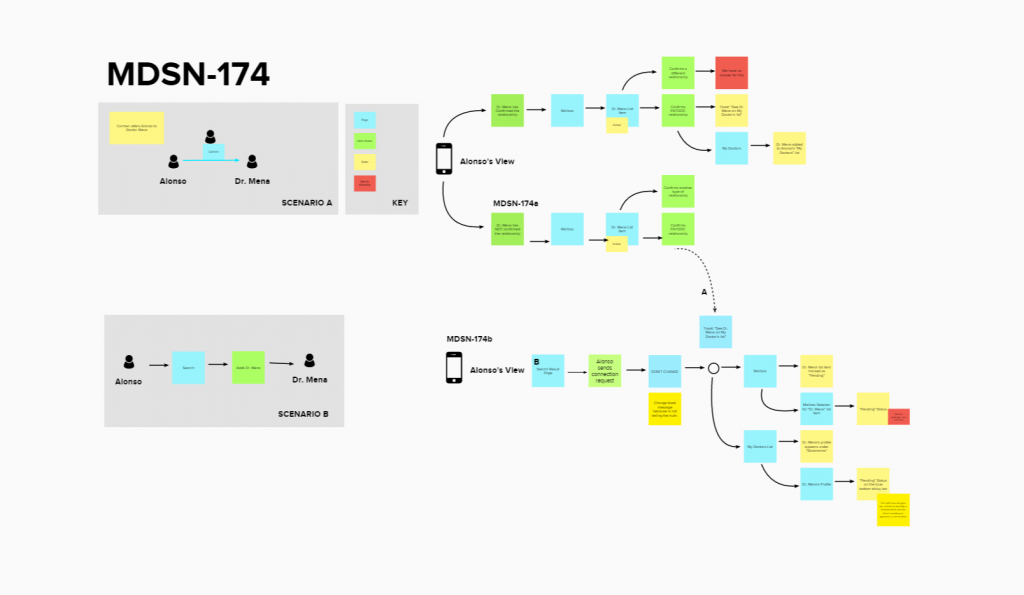

Often, our personas would help us understand work-flow or platform issues.

For instance, Linda (poor Linda), Carmen’s mother, was generally the victim of whatever medical crisis we envisioned. Our assumption was that her tech-savvy wouldn’t reach far beyond facebook, and that her husband, Juan, wouldn’t really have much to do with any of this at all. By building our characters in this way, every build decision took into consideration the way that their doctors could coordinate with Carmen to keep their records open to the family with little or no actual engagement with them. On the technical and interface side, we spent many an hour talking about the different ways ‘dependent accounts could be created, shared, and manipulated with the appropriate permissions in place without bothering the less tech-savvy members that each family would inevitably have.

These conversations also enabled us to have conversations about kids. Who has access to their account? How long? When do they take over? How does that happen?

This, in turn, gets to the core of why we used personas in development: It is easy to explain to new team members who these people are and how they act. It is sometimes quite difficult to say “If user A is a dependent of user B, but user C needs to have power of attorney over B so that they can make a decision, but A and C aren’t connected…” It is much easier to build a user story (development task) that says “Carmen enables Alonso to have power of attorney over Linda’s account.”

Personas are for Conversation.

Personas, like many frameworks in the development process, are a tool for conversation. Ultimately, building our persona set helped us synthesize the data from research and map it in a way that the team could find useful. By making personas of many different types of users, we’re able to build a vocabulary around our market and draw distinctions between value propositions that would resonate with each group.

Check out some other articles about how we used our Brand Personas for:

- MedicSana App; where our personas helped us understand user constraints and key flows.

- Brand Artifacts; where they helped us identify the messaging and visual design that we would use to communicate with our target market.

Or head back to the project homepage to view other posts about the MedicSana Project.

Personal Reflections: Brand Building on Small Teams

The practices of design research and persona building are specifically designed to encourage us to empathize with someone that has a different worldview and mental model than we do. In reality, it was a challenge to get everyone to see value in and contribute to the brand strategy and tenets.

At times, it can be hard for us to recognize and overcome our personal biases. For example, many of us in the technology industry are drawn to value propositions driven by “high-tech” or “innovative” framing. We have to recognize that while these aspects may be important to us, and we may love to brag about our “innovative solutions” to our peers in the techorati, our target market is driven by other concerns. At the end of the day, it is the mental model of our customers, not ourselves that matters most.

Team engagement can also be a challenge in many of these aspects. This is where it is crucial to support curiosity and teaching as a fundamental part of internal culture. The most friction – and the most growth – came from learning about practices other than our own expertise: both the marketing side of the house learning the constraints of technology, and the tech side learning about the philosophy and importance of brand building.

I’ve found that the most important skills in this area revolve around conversation moderation. In a good brainstorming session, every member of the team – no matter their background – generally brings a lot of creative thinking to the table. I believe that the mark of a good leader – and a goal that I’m always trying to improve upon – is the ability to facilitate a situation where everyone is excited to contribute and riff off of one another. This generally has a lot less to do with traditional “leading,” than creating a tone and an environment where people feel comfortable asking questions and making suggestions.

More about Me

Read more about the MedicSana project, other design case studies, or more about me on my homepage.